crocus et aglaé |

SPECTRE

BIPOLAIRE ou boîtes séparées ? |

ARGOS2003

|

Ces pages sont rédigées par un groupe de travail et sont, cela va mieux en le disant, SGDG.

Classification spectre bipolaire BPI et BPII bipolaire et unipolaire conséquences références

A). Il était une fois la dépression (Henry EY), classée en dépressions unipolaires et dépressions bipolaires. Dans son manuel de psychiatrie, Henry EY qui a été le leader de la psychiatrie française durant 40 ans décrivait la dépression bipolaire comme une dépression endogéne (d'origine biologique) dont les crises reviennent périodiquement et implacablement. Il la classait dans les psychoses.

En contraste, la dépression réactionelle, réaction normale et typique d'un deuil (deuil = tout événement extérieur grave), n'est pas récurrente et se termine normalement en 6 mois. Ce n'est pas une maladie, mais un mécanisme de réajustement de la personnalité. Les médicaments permettent de ramener la phase dépressive à un mois. C'est une névrose.

Tout cela est clair, net et précis. Mais il y a à la fin de cet exposé une phrase désabusée indiquant qu'il y a tous les intermédiaires en pratique. La belle construction théorique se réduit à quelques poteaux indicateurs dans un paysage chaotique.

B). Classification DSM IV. Le DSM-IV (ou son équivalent OMS le CIM-10) a classé les troubles de l'humeur en trois grandes catégories, les troubles dépressifs, les troubles bipolaires et les autres troubles de l'humeur. Le mouvement qui a donné naissance au DSM4 était la préoccupation des psychiatres américains de parler avec un seul langage des affections psychiatriques. Il s'agissait de définir des symptômes objectivement, déterminés d'après des questionnaires, et de regrouper les symptômes en syndromes avant de faire un diagnostic. Ce mouvement a permis d'objectiver la psychiatrie et de faire des études statistiques.

C). Une tendance de la fin des années 90 était de décrire des sous-catégories beaucoup plus précises de diagnostic TB 3,4,5,6,7 puis 1,5 2,5 etc.. L'espoir était de trouver des traitements précis s'appliquant a ces sous-catégories. Cet espoir a été déçu.

Une autre voie de recherche de recherche était de trouver des marqueurs biologiques de chaque type de trouble et de relier ces marqueurs aux études des neurotransmetteurs. Espoir encore une fois déçu.

La troisième voie de recherche était la voie génétique : trouver les génes des troubles bipolaires, ce qui permettrait de classer les différentes malfonctions La recherche des génes n'a pas échoué, mais s'est égaré dans un océan de complexité : il n'y a pas un géne, mais 11 génes impliqués, la causalité n'est pas directe mais c'est plutôt des facteurs de prédisposition, etc Voir les notes sur l' organisation biologique et sur les facteurs génétiques Il n'y a pas lien direct entre le génotype et le phénotype mais un passage par l'endophénotype. La recherche génétique actuellement se focalise sur la recherche de sous-groupes distingués.

TROUBLES BIPOLAIRES

| L'épisode dépressif majeur (EDM)

ou plutôt que majeur, caractérisé, voit l'humeur

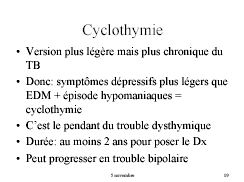

être dépressive durant un intervalle de temps important. La dysthymie est une humeur constamment dépressive, mais qui n'atteint pas une intensité négative importante. La cyclothymie voit se succéder très rapidement de courtes périodes d'humeur positives (exaltation) et négative (dépression). Le trouble bipolaire de type I (TBI) voit se succéder des périodes d'exaltation importante (manie) suivies de dépressions plus ou moins fortes et de période de calme (euthymie). Dans le trouble bipolaire de type II (TBII) la période d'exaltation est peu marquée et socialement bénigne. On parle d'hypomanie. Par contre, la période dépressive est souvent profonde et prolongée. On parle de cycles rapides quand il y a au moins quatre cycles exaltation-dépression par an. Les états mixtes sont des états ou des symptômes dépressifs coexistent avec des symptômes d'exaltation. ( cf chronique de N.Ghaemi) |

|

Voici ci-dessous la classification du DSM-IV TR. Les diagnostics sont posés lorsque des scores sont atteints aux questionnaires. Si le score reste en -dessous de la barre on parle de trouble bipolaire NOS (non spécifiés).

296.x Episode maniaque isolé

296.40 Episode le plus récent hypomaniaque

296.4x Episode le plus récent maniaque

296.5x Episode le plus récent dépressif

296.6x Episode le plus récent mixte

296.7 Episode le plus récent non spécifié

296.89 Trouble bipolaire II

spécifier (épisode actuel ou le plus récent) hypomaniaque/dépressif

301.13 trouble cyclothymique

AUTRES TROUBLES DE L'HUMEUR

De nombreuses affactions médicales ont pour symptômes secondaires des troubles psychiatriques.

296.83 Trouble de l'humeur due une affection médicale générale

291.8 Trouble de l'humeur induit par l'alcool

292.84 Trouble de l'humeur induit par d'autres substances

296.90 Troubles de l'humeur non spécifié

Le DSM-IV comporte des listes de symptomes qui permettent de donner des notes permettant de classer un malade dans une ou plusieurs affections spécifiées..

TB2,5, 3,5, ...

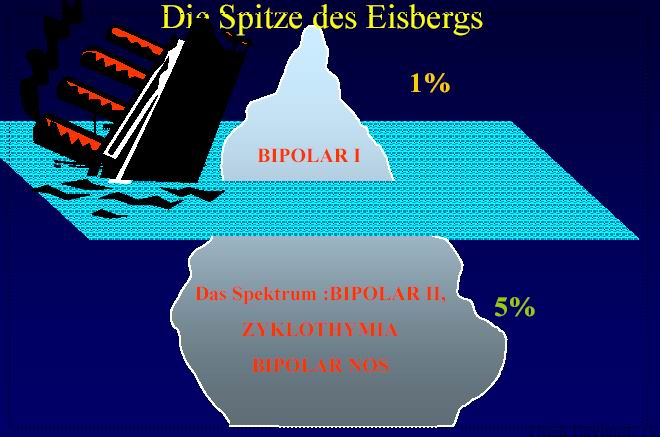

SPECTRE BIPOLAIRE

AKISKAL .et PINTO, en réaction avec le recherche de sous-groupes, les TB 3.14157 , ont mis l'accent sur la continuité statistique entre les différentes formes de trouble bipolaire. Pour cela il ont inventé la notion de spectre bipolaire . N.Ghaemi dans sa chronique Le spectre bipolaire : une forme fruste fait une analyse historique des limites des diagnostics des troubles de l'humeur.

BPI et BP II, continuité ou rupture

DEPRESSIONS RECURRENTES ET TB II

D'autres auteurs (en particulier l'école italienne autour de Benazzi) ont poursuivi dans cette voie "spectrale" et ont analysé la continuité ou discontinuité statistique avec les dépressions récurrentes et avec les dépressions unipolaires.

Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lattuada E, Cusin C, Smeraldi E. Clinical and demographic features of mood disorder subtypes.

Psychiatry Res. 2002 Nov 15;112(3):195-210.

Benazzi F. Clinical differences between bipolar II depression and unipolar major depressive disorder: lack of an effect of age.

J Affect Disord. 2003 Jul;75(2):191-5.

Dorz S, Borgherini G, Conforti D, Scarso C, Magni G. Depression in inpatients: bipolar vs unipolar.

Psychol Rep. 2003 Jun;92(3 Pt 1):1031-9.

Benazzi F. Bipolar II disorder and major depressive disorder: continuity or discontinuity?

World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;4(4):166-71.

Benazzi F. Bipolar II versus unipolar chronic depression: a 312-case study.

Compr Psychiatry 1999 Nov-Dec;40(6):418-21

Les résultats des analyses ont été en faveur d'une continuité du trouble bipolaire.

CONSEQUENCES SUR LES TRAITEMENTS

Si les troubles ont des affections distinctes (des boites séparées), à chaque boîte doit correspondre un ensemble de traitements. Si les troubles forment un continuum (le spectre bipolaire) le traitement doit varier aussi, de manière continue, en fonction des formes du troubles. L'enjeu diagnostique se double d'un enjeu thérapeutique.

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Maser J, Rice JA, Solomon DA, Keller MB.

The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders?

J Affect Disord. 2003 Jan;73(1-2):19-32.

"BACKGROUND: The present analyses were designed to compare the clinical characteristics and long-term episode course of Bipolar-I and Bipolar-II patients in order to help clarify the relationship between these disorders and to test the bipolar spectrum hypothesis. METHODS: The patient sample consisted of 135 definite RDC Bipolar-I (BP-I) and 71 definite RDC Bipolar-II patients who entered the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study (CDS) between 1978 and 1981; and were followed systematically for up to 20 years. Groups were compared on demographic and clinical characteristics at intake, and lifetime comorbidity of anxiety and substance use disorders. Subsets of patients were compared on the number and type of affective episodes and the duration of inter-episode well intervals observed during a 10-year period following their resolution of the intake affective episode. RESULTS: BP-I and BP-II had similar demographic characteristics and ages of onset of their first affective episode. Both disorders had more lifetime comorbid substance abuse disorders than the general population. BP-II had a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in general, and social and simple phobias in particular, compared to BP-I. Intake episodes of BP-I were significantly more acutely severe. BP-II patietns had a substantially more chronic course, with significantly more major and minor depressive episodes and shorter inter-episode well intervals. BP-II patients were prescribed somatic treatment a substantially lower percentage of time during and between affective episodes. LIMITATIONS: BP-I patients with severe manic course are less likely to be retained in long-term follow-up, whereas the reverse might be true for BP-II patients who are significantly more prone to depression (i.e., patients with less inclination to depression and with good prognosis may have dropped out in greater proportions); this could increase the gap in long term course characteristics between the two samples. The greater chronicity of BP-II may be due, in part, to the fact that the patients were prescribed somatic treatments substantially less often both during and between affective episodes. CONCLUSIONS: The variety in severity of the affective episodes shows that bipolar disorders, similar to unipolar disorders, are expressed longitudinally during their course as a dimensional illness. The similarities of the clinical phenotypes of BP-I and BP-II, suggest that BP-I and BP-II are likely to exist in a disease spectrum. They are, however, sufficiently distinct in terms of long-term course (i.e., BP-I with more severe episodes, and BP-II more chronic with a predominantly depressive course), that they are best classified as two separate subtypes in the official classification systems." [Abstract]

Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Maser J, Coryell W, Solomon D, Endicott J, Keller M.

Long-term symptomatic status of bipolar I vs. bipolar II disorders.

Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003 Jun;6(2):127-137.

"Weekly affective symptom severity and polarity were compared in 135 bipolar I (BP I) and 71 bipolar II (BP II) patients during up to 20 yr of prospective symptomatic follow-up. The course of BP I and BP II was chronic; patients were symptomatic approximately half of all follow-up weeks (BP I 46.6% and BP II 55.8% of weeks). Most bipolar disorder research has concentrated on episodes of MDD and mania and yet minor and subsyndromal symptoms are three times more common during the long-term course. Weeks with depressive symptoms predominated over manichypomanic symptoms in both disorders (31) in BP I and BP II at 371 in a largely depressive course (depressive symptoms=59.1% of weeks vs. hypomanic=1.9% of weeks). BP I patients had more weeks of cyclingmixed polarity, hypomanic and subsyndromal hypomanic symptoms. Weekly symptom severity and polarity fluctuated frequently within the same bipolar patient, in which the longitudinal symptomatic expression of BP I and BP II is dimensional in nature involving all levels of affective symptom severity of mania and depression. Although BP I is more severe, BP II with its intensely chronic depressive features is not simply the lesser of the bipolar disorders; it is also a serious illness, more so than previously thought (for instance, as described in DSM-IV and ICP-10). It is likely that this conventional view is the reason why BP II patients were prescribed pharmacological treatments significantly less often when acutely symptomatic and during intervals between episodes. Taken together with previous research by us on the long-term structure of unipolar depression, we submit that the thrust of our work during the past decade supports classic notions of a broader affective disorder spectrum, bringing bipolarity and recurrent unipolarity closer together. However the genetic variation underlying such a putative spectrum remains to be clarified." [Abstract]

Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lattuada E, Cusin C, Smeraldi E.

Clinical and demographic features of mood disorder subtypes.

Psychiatry Res. 2002 Nov 15;112(3):195-210.

"The aim of this study was to investigate demographic, clinical and symptomatologic features of the following mood disorder subtypes: bipolar disorder I (BP-I); bipolar disorder II (BP-II); major depressive disorder, recurrent (MDR); and major depressive episode, single episode (MDSE). A total of 1832 patients with mood disorders (BP-I=863, BP-II=141, MDR=708, and MDSE=120) were included in our study. The patients were assessed using structured diagnostic interviews and the operational criteria for psychotic illness checklist (n=885), the Hamilton depression rating scale (n=167), and the social adjustment scale (n=305). The BP-I patients were younger; had more hospital admissions; presented a more severe form of symptomatology in terms of psychotic symptoms, disorganization, and atypical features; and showed less insight into their disorder than patients in the other groups. Compared with the major depressive subgroups, BP-I patients were more likely to have an earlier age at onset, an earlier first lifetime psychiatric treatment, and a greater number of illness episodes. BP-II patients had a higher suicide risk than both BP-I and MDSE patients. MDSE patients presented less severe symptomatology, lower age at observation, and a higher number of males. The retrospective approach and the selection constraints due to the inclusion criteria are the main limitations of the study. Our data support the view that BP-I disorder is quite different from the remaining mood disorders from a demographic and clinical perspective, with BP-II disorder having an intermediate position to MDR and MDSE, that is, as a less severe disorder. This finding may help in the search for the biological basis of mood disorders." [Abstract]

Benazzi F.

Clinical differences between bipolar II depression and unipolar major depressive disorder: lack of an effect of age.

J Affect Disord. 2003 Jul;75(2):191-5.

"BACKGROUND: Inconsistent clinical differences were reported in bipolar II versus unipolar depression. Age difference may be a confounding factor. Study aims were to describe the clinical and family history features of bipolar II versus unipolar depression, and to control for the possible confounding effect of age on clinical features. METHODS: Consecutive 126 unipolar and 187 bipolar II major depressive episode (MDE) outpatients were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Variables studied were gender, age, age of onset, MDE recurrences, axis I comorbidity, MDE severity, psychotic, melancholic, and atypical features, depression chronicity, melancholic, atypical, and hypomanic symptoms, depressive mixed state-DMX3 (MDE+three or more concurrent hypomanic symptoms), and mood disorders family history. The effect of age on clinical differences was controlled by logistic regression (by adding age as an independent variable after each independent variable). RESULTS: Bipolar II had significantly lower age, lower age of onset, more recurrences, more atypical features, more DMX3, more family history of bipolar II and MDE. Almost all the clinical differences found significant in the first analysis resulted still significant when controlled for age. LIMITATIONS: Single interviewer, non-blind, cross-sectional assessment, bipolar II diagnosis based on history. CONCLUSIONS: Results confirmed previous findings, and showed that bipolar II-unipolar MDE clinical differences were not related to age." [Abstract]

Dorz S, Borgherini G, Conforti D, Scarso C, Magni G.

Depression in inpatients: bipolar vs unipolar.

Psychol Rep. 2003 Jun;92(3 Pt 1):1031-9.

"162 depressed inpatients were divided into three diagnostic groups to compare patterns of sociodemographic characteristics, psychopathology, and psychosocial: 35 had a single episode of major depression, 96 had recurrent major depression, and 31 had a bipolar disorder. Psychopathology and psychosocial functioning were measured by clinician-rated scales, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Clinical Global Impression, and self-rating scales, Symptom Checklist-90, Social Support Questionnaire, Social Adjustment Scale. The three groups were comparable on sociodemographic variables, with the exception of education. Univariate analyses showed a similar social impairment as measured by Social Support Questionnaire, Social Adjustment Scale, and no significant differences were recorded for the psychopathology when the total test scores (Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Clinical Global Index, Symptom Checklist-90) were evaluated. Some differences emerged for single items in the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale and Symptom Checklist-90. These findings suggest a substantial similarity among the three groups. Results are discussed in terms of the clinical similarities between unipolar and bipolar patients during a depressive episode as well as the limitations of cross-sectional study implies." [Abstract]

Benazzi F.

Bipolar II disorder and major depressive disorder: continuity or discontinuity?

World J Biol Psychiatry. 2003 Oct;4(4):166-71.

"AIM: To find if bipolar II disorder (BPII) and major depressive disorder (MDD) were distinct categories or overlapping syndromes. METHODS: 308 BPII and 236 MDD outpatients, presenting for major depressive episode (MDE) treatment, were interviewed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. History of mania and hypomania, and hypomanic symptoms present during MDE, were systematically investigated. Presence of zones of rarity between BPII and MDD depressive syndromes was assessed. Atypical and hypomanic symptoms were chosen because atypical features and depressive mixed state (ie, MDE plus more than 2 concurrent hypomanic symptoms, according to Akiskal and Benazzi 2003) were often reported to distinguish BPII from MDD depressive syndromes (more common in BPII). If BPII were a distinct category, distributions of these symptoms should show zones of rarity between BPII and MDD depressive syndromes. Histograms and Kernel density estimate were used to study distributions of these symptoms. RESULTS: BPII had significantly more atypical features and depressive mixed state than MDD. Histograms and Kernel density estimate curves of distributions of atypical and hypomanic symptoms in the entire sample did not show zones of rarity. CONCLUSIONS: Finding no zones of rarity supports a continuity between BPII and MDD (meaning partly overlapping disorders without clear boundaries)." [Abstract]

Benazzi F.

Bipolar II versus unipolar chronic depression: a 312-case study.

Compr Psychiatry 1999 Nov-Dec;40(6):418-21

"Differences between bipolar II depression and unipolar depression have been reported, such as a lower age at onset and more atypical features in bipolar II depression. The aim of the present study was to compare chronic/nonchronic bipolar II depression with chronic/nonchronic unipolar depression to determine whether the reported differences are present when chronicity is taken into account. Three hundred twelve outpatients in a bipolar II/unipolar major depressive episode were assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Clinician Version (SCID-CV), the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale. No significant difference was found between chronic bipolar II and chronic unipolar depression (age at intake and onset, gender, duration of illness, recurrences, psychosis, atypical features, axis I comorbidity, and severity). A significantly lower age at onset and more atypical features were observed when comparing chronic/nonchronic bipolar II with nonchronic unipolar depression. These findings suggest that differences reported between bipolar II and unipolar depression are mainly due to nonchronic unipolar depression. Chronic unipolar depression may be a subtype intermediate between bipolar II depression and nonchronic unipolar depression." [Abstract]

The Bipolar Spectrum: A Valid Forme Fruste?

by S. Nassir Ghaemi, M.D. http://www.mhsource.com/bipolar/insight0128gha.htmlClosely related to the question of my previous column-whether or not bipolar disorder (BD) is misdiagnosed-is the issue of how to define bipolar disorder. For most of this century, American psychiatry's definition of manic-depressive illness has tended to be rather narrow (while those of schizophrenia and depression have been correspondingly broad). Over the last two decades, the diagnostic limits of schizophrenia have been narrowed greatly and those of affective disorders (including BD) broadened somewhat. This trend has led to increasing discussion of the concept of a "bipolar spectrum." Is this concept valid and useful?

Historically, the original conceptions underlying BD always reflected the controversy over whether to view the illness broadly or narrowly. (This history is best reviewed in Baldessarini [2000], and Goodwin and Jamison [1990]). In the mid- to late 19th century, leaders in French psychiatry identified mania and depression; they tended to diagnose manic-depressive conditions narrowly, with many subgroupings. In the late 19th and early 20th century, the German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin first argued for a neat division of all psychotic syndromes into schizophrenia (narrowly conceived and limited to a small number of individuals in the population) and manic-depressive illness (broadly conceived and including what today we would call recurrent major depression). Kraepelin's work gained much influence for a few decades, but it was soon eclipsed by the rise of interest in Freud. Freud had little interest in diagnosis, and thus the controversy between Kraepelin's broad view and the earlier narrower French perspective ebbed. In the 1950s and 1960s, some European psychiatrists resuscitated the earlier French conceptions and made the distinction between bipolar (mania being present) and unipolar (mania not present) affective illnesses. Genetic and outcome research supported this model and led to its acceptance in American nosology with DSM-III in 1980. More recently, BD has been further divided into type I (mania present) and type II (hypomania present, a milder form of manic symptoms) in DSM-IV.

Thus, if one begins with Kraepelin's original broad concept of manic-depressive illness, mainstream psychiatry has moved to a more narrow description of BD (type I or II) and unipolar depression. For the last half century, this has meant that most clinicians have not diagnosed BD unless a patient was frankly, overtly and unequivocally manic (usually extremely agitated, psychotic and hospitalized). The tendency has been for everyone else to receive a diagnosis of unipolar depression or schizophrenia. This scenario is a source of some wonder. The textbooks say, and everyone claims to agree, that unipolar depression and schizophrenia are diagnoses of exclusion. One is supposed to rule out past mania before diagnosing unipolar depression in a nonpsychotic depressed individual; one is also supposed to rule out mania before diagnosing schizophrenia in a psychotic individual. Yet, in each case, since mania has only been diagnosed when extreme and severe, it is my opinion that the tendency is to underdiagnose BD. (See my previous columns for empirical studies that support this notion.)

The concept of the bipolar spectrum is, in many senses, a reversion to the original Kraepelinian perspective. Today, when referring to the bipolar spectrum, the clinician is first making the statement that mania is not necessary for the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Hypomania would do, being defined as milder manic symptoms lasting a few days or more that are not associated with any significant social or occupational dysfunction. This last qualifier is extremely important. With hypomania, one has no difficulties; in fact, one is functioning more effectively in life. I believe that hypomania is the only diagnosis in DSM-IV that does not have, as one of its criteria, the presence of significant social or occupational dysfunction. This makes type II BD (hypomania and depression) unique-the defining diagnostic feature (hypomania) occurs when someone is feeling well. This, of course, often makes it difficult for individuals and clinicians to recognize. The problem with bipolar II disorder, consequently, is not hypomania, but the inevitable depressions that precede or follow it.

Bipolar II disorder is becoming more and more accepted as a valid diagnosis, although it remains a quite unreliable one, i.e., clinicians often do not agree on what to call hypomania and what to call normal mood. In my opinion, most clinicians are culturally biased to overdiagnose normality and underdiagnose hypomania.

The other part of the bipolar spectrum would be the category of NOS (not otherwise specified). (The evidence for the following discussion is best detailed in Akiskal [1996].) This could include individuals with a family history of type I BD and those who have hypomania only on antidepressants. Other potential "soft signs" of BD include atypical (increased sleep and appetite) and psychotic depressive episodes (both are more common in bipolar than unipolar depression); early age of onset of depressive illness; many brief recurrent depressive episodes (Kraepelin included them in his concept of manic-depressive illness); transient antidepressant response ("poop-out," meaning acute improvement but later relapse); and "hyperthymic" baseline personality when not depressed (a kind of chronic hypomania that is not brief and episodic but rather seems to be one's basic personality). A single soft sign is not diagnostic of the bipolar spectrum, but the more soft signs that exist, the increased likelihood that it is bipolar spectrum rather than unipolar depressive illness.

This broad bipolar spectrum view stems from observations regarding treatment response with lithium and antidepressants and, thus, has practical utility. Bipolar spectrum patients may be less likely to respond to antidepressants (thus representing part of that pool of people diagnosed with treatment-resistant depression) and may be more likely to respond to mood stabilizers (alone or along with antidepressants) (Akiskal, 1996).

If valid, the bipolar spectrum concept would have the advantage of redressing the imbalance in diagnostic perspectives and influencing clinicians to diagnose milder cases of mania and hypomania. An increase in diagnosis of the bipolar spectrum would also narrow down the diagnostic range of unipolar depression to more realistic and accurate levels. This is the perspective of individuals, myself included, who are attracted to the concept of the bipolar spectrum.

What can be said against the bipolar spectrum? First, there is little research to validate or invalidate it. To some extent, this is a circular problem: Since the field has generally ignored anything but classic bipolar I disorder, researchers and grant-giving agencies are often wary of giving money for research on a new and poorly documented concept such as the bipolar spectrum. I ran into this problem a few years ago when gabapentin (Neurontin), a new medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for epilepsy, was to be studied for use in psychiatric conditions. I suggested that the drug be studied in type II bipolar depression along with, or perhaps instead of, type I BD. In my early clinical experience, I found limited efficacy for the medication in type I BD, but found suggested efficacy in type II bipolar illness. If gabapentin had mild to moderate mood-stabilizing effects, it might not work in type I BD, but it might have benefits in the milder parts of the bipolar spectrum (Ghaemi et al., 1998). This suggestion was not accepted on the grounds that the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder was unreliable (clinicians often disagree in defining hypomania), and that the diagnosis itself was too vague to be worth studying. Another factor may have been that the FDA has never recognized any bipolar diagnosis other than mania, and thus studying hypomania or the bipolar spectrum would not necessarily meet with any support on the part of federal regulators when seeking a treatment indication. Gabapentin went on to be ineffective in double-blind research on bipolar I disorder (Pande, 1999), and controlled research in the bipolar spectrum was never conducted.

The other major criticism made of the bipolar spectrum-in my opinion, the one with the most merit-is that the spectrum concept waters down the definition of bipolar disorder so much that it would impair biological research (Baldessarini, 2000). In general, for biological studies into the etiology and pathophysiology of a disease, it is necessary for the clinical definition of the condition to be as precise and homogeneous as possible. Since the spectrum concept is, by definition, broad and heterogeneous, it might impair the ability of biological studies to find the underlying problems leading to BD. This is a real concern.

One solution would be a "two-hat" answer. Wearing the researcher's hat, I would continue to focus on narrow, clearly defined bipolar I disorder. Wearing the clinician's hat, I would broaden my view to include the bipolar spectrum. Is this proposed solution inconsistent? Yes, but as Emerson long ago pointed out, consistency is not necessarily a component of truth. Whatever the biological etiology, the clinical manifestations of that etiology can vary immensely, especially as those manifestations might be influenced by varied environmental and other factors. This has long been recognized in medicine, where the concept of the forme fruste has long been invoked to describe mild, subtle forms of specific diseases.

Does bipolar disorder have a forme fruste? Probably. But we need to do more work on describing, defining and validating its characteristics.

Dr. Ghaemi is a research psychiatrist in the Psychopharmacology Program at Cambridge Hospital and an instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

References

Akiskal HS (1996), The prevalent clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders: beyond DSM-IV. J Clin Psychopharmacol 16(2 suppl 1):4S-14S.

Baldessarini RJ (2000), A plea for the integrity of the bipolar disorder concept. Bipolar Disorders 2(1):3-7.

Ghaemi SN, Katzow JJ, Desai SP, Goodwin FK (1998), Gabapentin treatment of mood disorders: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychiatry 59(8):426-429.

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR (1990), Manic-Depressive Illness. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Mixed States: Broad or Narrow?

by S. Nassir Ghaemi, M.D. http://www.mhsource.com/bipolar/insight1001gha.htmlI have previously discussed in this column several controversial questions related to bipolar disorder. I have expressed my opinion and presented some evidence that bipolar disorder is at times misdiagnosed, frequently as unipolar depression, and that antidepressants often are overused in the treatment of bipolar disorder. I have also suggested that a broad notion of the bipolar spectrum is likely to be clinically and scientifically accurate. Some of these views touch on the question of mixed states, which is the subject of this column.

Mixed episodes are currently defined by DSM-IV as the occurrence of a full manic episode and a full major depressive episode at the same time (with the exception that the duration of a mixed episode can be a minimum of one week, compared to two weeks for pure major depression). The inclusion of mixed episodes in DSM nosology is relatively new, and it appears that the criteria have been made deliberately narrow, perhaps to discourage overdiagnosis. Earlier definitions of mixed states were broader.

Like so much else related to bipolar disorder, the concept of mixed states dates back to Emil Kraepelin, who described two basic forms. (This subject has been reviewed well by Akiskal and colleagues [2000]). One type of mixed state was characterized predominantly by manic symptoms, with a few depressive symptoms also present. This has come to be called dysphoric mania. The other type was characterized predominantly by depressive symptoms, with a few manic symptoms also present. This has been referred to as agitated depression. For Kraepelin, and for those who would follow his approach to nosology in detail, both dysphoric mania and agitated depression would be considered mixed states of manic-depressive illness.

Part of the uncertainty concerning mixed states relates to the concept of the bipolar spectrum. Where should we draw the line on dysphoric mania, as opposed to pure mania? Where should we draw the line on agitated depression (viewed as a mixed state), as opposed to pure depression? How are we to decide?

As I have discussed previously in this column ("The Bipolar Spectrum: A Valid Forme Fruste?"), questions of diagnostic validity in psychiatry are difficult because of the lack of a gold standard. It is convention to base psychiatric diagnostic validity on five factors, and the more these factors converge and agree, the greater the likely validity of a diagnostic group. To recap, these factors are: 1) clinical signs and symptoms, 2) course, 3) family history/genetics, 4) biological markers, and 5) treatment response (Robins and Guze, 1970). Let us try to apply these diagnostic validators to different concepts of mixed states.

Beginning with dysphoric mania, how many depressive symptoms are needed to distinguish this state from pure mania: one, two, three? Since DSM-IV requires that full symptom criteria for major depression be met, the current nosology would answer that five depressive symptoms are needed. In one study, the presence of one depressive symptom (e.g., isolated depressed mood) predicted poor response to lithium and good response to an anticonvulsant, divalproex (Depakote) (Swann et al., 1997). This is one validator of diagnosis, since anticonvulsants generally are more effective in mixed states than lithium. However, treatment response is probably the weakest single validator of a diagnosis. This is because psychotropic medications are generally nonspecific--they are effective in multiple diagnoses, rather than being magic bullets for one diagnosis. Nonetheless, that observation should raise some doubt in one’s mind about an extremely narrow definition of mixed state. Other studies suggest that two or three depressive symptoms are associated with other features of mixed states, such as suicidality and poor outcome (Akiskal et al., 2000). In this same article, Akiskal et al. suggest that a broad definition of mixed states may be clinically useful.

One of the key confounding aspects of mixed states is the presence of depressive symptoms. Frequently clinicians and patients focus on the depressive symptoms and may fail to notice that manic symptoms are also present. In any depressed patient, it is important to rule out manic symptoms.

Antidepressant-induced manic symptoms sometimes seem to be of the mixed variety. Such mixed states may not be recognized as manic conditions, but rather be labeled “activation” or “agitation.” I often wonder whether some cases of antidepressant-related suicidality may not represent mixed states.

Obviously, the definition of mixed states is still not clear. It seems accepted that mixed states occur, but how frequently and where one draws the line between them and pure mood states are still subjects of some conjecture.

Dr. Ghaemi is director of the Bipolar Disorder Research Program at Cambridge Hospital and assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, Mass.

References

Akiskal HS, Bourgeois ML, Angst J et al. (2000), Re-evaluating the prevalence of and diagnostic composition within the broad clinical spectrum of bipolar disorders. J Affect Disord 59(suppl 1):S5-S30.

Robins E, Guze SB (1970), Establishment of diagnostic validity in psychiatric illness: its application to schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 126(7):983-987.

Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D et al. (1997), Depression during mania. Treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54(1):37-42[see comment].