Notes sur les

conséquences et complications

Notes sur les

conséquences et complications  Notes sur les

conséquences et complications Notes sur les

conséquences et complications |

ARGOS2003 |

Jeudi 11 décembre 2003 :

Conséquences et complications

Les principaux documents de

référence sont

indiqués en fin. Il n'est pas question d'être exhaustif sur un tel

sujet, aussi a-t-on privilégie les documents récents faisant autorité

(rapports de recherche) et

les rares documents en français. La presse de vulgarisation

médicale a

été volontairement écartée.

by Leonardo Tondo, MD, Ross J. Baldessarini, MD, and John Hennen, PhD

ABSTRACT

Can timely diagnosis and treatment of depression reduce the risk of suicide? Studies of treatment effects on mortality in major mood disorders remain rare and are widely considered difficult to carry out ethically. Despite close associations of suicide with major affective disorders and related comorbidity, the available evidence is inconclusive regarding for sustained reductions of suicide risk by most mood-altering treatments, including antidepressants. Studies designed to evaluate clinical benefits of mood-stabilizing treatments in bipolar disorders, however, provide comparisons of suicidal rates with and without treatment or under different treatment conditions. This emerging body of research provides consistent evidence of reduced rates of suicides and attempts during long-term treatment with lithium. This effect may not generalize to proposed alternatives, particularly carbamazepine. Our recent international collaborative studies found compelling evidence for prolonged reduction of suicidal risks during treatment with lithium, as well as sharp increases soon after its discontinuation, all in close association with depressive recurrences. Depression was markedly reduced, and suicide attempts were less frequent, when lithium was discontinued gradually. These findings indicate that studies of the effects of long-term treatment on suicide risk are feasible and that more timely diagnosis and treatment for all forms of major depression, but particularly for bipolar depression, should further reduce suicide risk.

INTRODUCTION

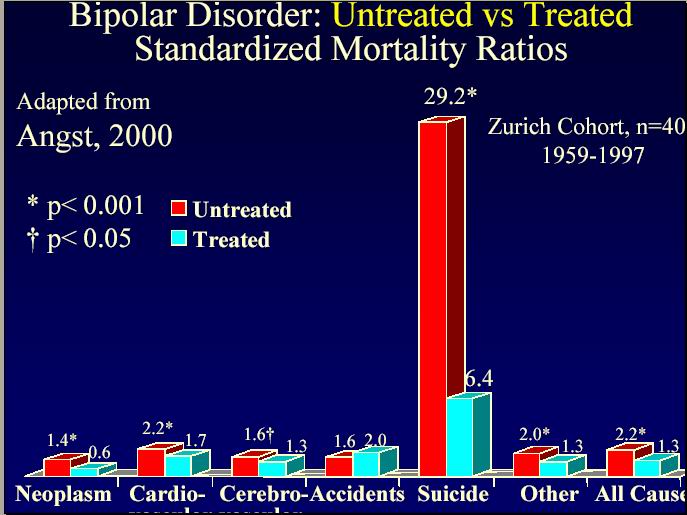

Risk of premature mortality significantly increases in bipolar manic-depressive disorders.(1-12) Mortal risk arises from very high rates of suicide in all major affective disorders, which are at least as great in bipolar illness as in recurrent major depression.(1, 2, 13-16) A review of 30 studies of bipolar disorder patients found that 19% of deaths (range in studies from 6% to 60%) were due to suicide.(2) Rates may be lower in never-hospitalized patients, however.(6, 11, 12) In addition to suicide, mortality is probably also increased due to comorbid, stress-related, medical disorders, including cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases. (3-5, 7, 10) High rates of comorbid substance use disorders contribute further to both medical mortality and to suicidal risk (11, 17), especially in young persons (18), in whom violence and suicide are leading causes of death.(11, 12, 19)

Suicide is strongly associated with concurrent depression in all forms of the common major affective disorders.(2, 9, 20, 21) Lifetime morbid risk for major depression may be as high as 10%, and lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorders probably exceeds 2% of the general population if cases of type II bipolar syndrome (depression with hypomania) are included. (2, 22, 23) Remarkably, however, only a minority of persons affected with these highly prevalent, often lethal, but usually treatable major affective disorders receive appropriate diagnosis and treatment, and often only after years of delay or partial treatment. (8 ,9, 22, 24-28) Despite grave clinical, social, and economic effects of suicide, and its very common association with mood disorders, specific studies on the effects of mood-altering treatments on suicidal risk remain remarkably uncommon and inadequate to guide either rational clinical practice or sound public health policy.(7, 8, 11, 12, 22, 29, 30)

In view of the clinical and public health importance of suicide in manic-depressive disorders, and the rarity of evidence proving that modern mood-altering treatments reduce suicide rates, an emerging body of research has been reviewed. It indicates a significant, sustained, and possibly unique reduction of suicidal behavior during long-term treatment with lithium salts. These important effects have not been demonstrated with other mood-altering treatments.

THERAPEUTICS RESEARCH IN SUICIDE

Despite broad clinical use and intensive study of antidepressants for four decades, evidence that they specifically alter suicidal behavior or reduce long-term suicidal risk remains meager and inconclusive.(9, 11, 17, 31-37) The introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other modern antidepressants that are much less toxic on acute overdose than older drugs appears not to have been associated with a decrease in suicide rates.(34, 38) Instead, their introduction may have been associated with a shift toward more lethal means of self-destruction.(39) We found only one report of a significantly lower rate of suicide in depressed patients treated with antidepressants compared to placebo (0.65% vs 2.78% per year), with an even lower rate with an SSRI than with other antidepressants (0.50% vs 1.38% per year).(37) Nevertheless, suicide rates during antidepressant treatment in that study were far greater than the general population rate of 0.010% to 0.015% per year, uncorrected for persons with mood disorders and other illnesses associated with increased suicide rates.(40)

Bipolar depression accounts for much or most of the time one is stricken with bipolar disorder (24) and can be disabling or fatal.(2, 7, 11, 12) Remarkably, however, the treatment of this syndrome remains much less studied than depressive to manic, agitated or psychotic unipolar major depression.(24, 38, 41) Indeed, bipolarity is typically a criterion for exclusion from studies of antidepressant treatment, apparently to avoid risks of switching from depressive to manic, agitated or psychotic phases when patients are not protected with lithium or another mood-stabilizing agent.(38)

Reasons for the rarity of studies of the effects of modern psychiatric treatments on suicide rates are not entirely clear. Therapeutic research on suicide is appropriately constrained ethically when fatality is a potential outcome, and particularly when discontinuation of ongoing treatment is required in a research protocol. Treatment discontinuation is increasingly recognized as being followed by at least temporary, sharp increases in morbidity that may exceed the morbid risk associated with untreated illness. This evidently iatrogenic phenomenon has been associated with discontinuation of maintenance treatment with lithium (42-46), anti-depressants (47), and other psychotropic agents.(44, 48) Mortality can also increase following treatment discontinuation. (9, 11, 21, 22) Such reactions can complicate clinical management. Moreover, they may also confound many research findings in that typically reported "drug vs. placebo" comparisons may not represent straightforward contrasts of treated vs untreated subjects when placebo conditions represent discontinuation of an ongoing treatment.

Avoiding such risks, most studies of treatment effects on suicide have been naturalistic or have examined suicidal behavior post-hoc as an unintended outcome of controlled treatment trials. Such studies have provided evidence that maintenance treatment with lithium is associated with a strong, and possibly unique, protective effect against suicidal behavior in major affective disorders, and particularly in bipolar syndromes. (6, 8, 11, 12, 21, 22, 49-56) Moreover, lithium's protective effect may extend more broadly to all causes of mortality in these disorders, although this possibility remains much less studied. (2, 3, 5, 7)

SUICIDE RATES ON AND OFF LITHIUM

We recently evaluated all available studies of lithium and suicide since the emergence of long-term lithium maintenance treatment in manic depressive disorders in the early 1970s. Studies were identified by computerized literature searches and cross-referencing from publications on the topic, as well as by discussing the aims of the study with colleagues who have conducted research on lithium treatment or who may have had access to unpublished data on suicide rates in bipolar disorder patients. We sought data permitting estimates of rates of attempted or completed suicides in bipolar patients or mixed samples of patients with major affective disorders that included bipolar manic-depressives. Suicide rates during maintenance lithium treatment were compared with rates after discontinuation of lithium or in similar untreated samples when such data were available.

Suicide rates during long-term lithium treatment were determined for each study, and, when available, rates for patients discontinued from lithium or for comparable patients not treated with a mood stabilizer were also determined. Suicide rates during lithium treatment were not significantly greater with larger numbers of subjects or longer follow-up. However, many of the available reports were flawed in one or more respects. Limitations included: (1) a common lack of control over treatments other than lithium; (2) incomplete separation by diagnosis or provision of separate rates for suicide attempts and completions in some studies; (3) a lack of comparisons of treated and untreated periods within subjects or between groups; (4) study of fewer than 50 subjects/treatment conditions despite the relatively low frequency of suicide; (5) inconsistent or imprecise reporting of time-at-risk (the amount of time the patient was absent); and (6) selection of patients with previous suicide attempts that may show bias toward increased suicide rates in some studies. Some of these deficiencies were resolved by contacting authors directly. Despite their limitations, we believe that the available data are of sufficient quality and importance to encourage further evaluation.

Table 1 summarizes available data concerning rates of suicides and attempts among manic-depressive patients on or off lithium, based on previously reported (6) and new, unpublished meta-analyses. The results indicate an overall reduction of risk by nearly seven fold, from 1.78 to 0.26 suicide attempts and suicides per 100 patient-years at risk (or percent of persons/year). In another more recent, quantitative meta-analysis (L.T., unpublished, 1999), we evaluated fatality rates ascribed to suicide in the same studies as well as in additional previously unreported data kindly provided by international collaborators. In the latter analysis, based on results from 18 studies and more than 5,900 manic-depressive subjects, we found a similar reduction of risk from a suicide rate averaging 1.83 ± 0.26 suicides per 100 patient-years in patients not treated with lithium (either after discontinuing or in parallel groups not given lithium) to 0.26 ± 0.11 suicides per 100 patient-years in patients on lithium.

IMPLICATIONS OF FINDINGS

The present findings derived from the research literature on lithium and suicide risk indicate substantial protection against suicide attempts and fatalities during long-term lithium treatment in patients with bipolar manic-depressive disorders, or in mixed groups of major affective disorder subjects that included bipolar patients. While this evidence is strong and consistent overall, the relative infrequency of suicide and limited size of many studies required pooling of data to observe statistically significant effect that was not found in several individual studies. Large samples and lengthy times-at-risk, or pooling of data across studies, are likely to be required in future studies of treatment effects on suicide rates.

It is also important to emphasize that the observed, pooled, residual risk of suicides while on lithium, though much lower than without lithium treatment, is still large, and greatly exceeds general population rates. The average suicide rate during lithium maintenance treatment, at 0.26% per year (Table 1), is more than 20 times greater than the annual general population rate of about 0.010% to 0.015%, which also includes suicides associated with psychiatric illnesses.(11, 40) The evidently incomplete protection against suicide associated with lithium treatment may reflect limitations in the effectiveness of the treatment itself and, very likely, potential noncompliance to long-term maintenance therapy.

Since suicidal behavior is closely associated with concurrent depressive or dysphoric mixed states in bipolar disorder patients (9, 11, 20), it is likely that residual risk for suicide is associated with incomplete protection against recurrences of bipolar depressive or mixed mood states. Lithium has traditionally been considered to provide better protection against mania than against bipolar depression.(27, 38) In a recent study of more than 300 bipolar I and II subjects, we found that depressive morbidity was reduced from 0.85 to 0.41 episodes per year (a 52% improvement) and time ill was reduced from 24.3% to 10.6% (a 56% reduction) before vs during lithium maintenance treatment.(23) Improvements in mania or hypomania were somewhat larger, at 70% for episode rates and 66% for percentage of time manic, with even greater improvement in hypomania in type 11 cases (84% fewer episodes and 80% less time hypomanic). Corresponding suicide rates fell from 2.3 to 0.36 suicide attempts per 100 patient-years (an 85% improvement) during vs before lithium maintenance treatment. (9, 20) The present findings indicate an 85% to crude sparing of completed suicides and attempts (1.78 to 0.26% per year; see Table 1). These comparisons suggest that protective effects of lithium rank: suicide attempts or suicides³ hypomania>mania>bipolar depression. Since suicide is closely associated with depression (11, 20), it follows that better protection against bipolar depression must be a key to limiting suicidal risk in bipolar disorders.

It is not clear whether reduction of suicide rates during lithium maintenance reflects simply the mood-stabilizing effect of lithium, or if other properties of lithium also contribute. In addition to protection from recurrences of bipolar depressive and mixed-mood states closely associated with suicidal behavior, important associated benefits of lithium treatment possibly also contribute to reduction of suicide risk. These may include improvements in overall emotional stability, interpersonal relationships and sustained clinical follow-up, vocational functioning, self-esteem, and perhaps reduced comorbid substance abuse.

An alternative possibility is that lithium may have a distinct psychobiological action on suicidal and perhaps other aggressive behaviors, possibly reflecting serotonin-enhancing actions of lithium in limbic forebrain. (38, 57) This hypothesis accords with growing evidence of an association between cerebral deficiency of serotonin functioning and suicidal or other aggressive behaviors. (58-59) If lithium protects against suicide through its central serotonergic activity, then proposed alternatives to lithium with dissimilar pharmacodynamics may not be equally protective against suicide. Specifically, mood-stabilizing agents that lack serotonin enhancing properties, including most anti-convulsants (27, 38), might not protect against suicide as well as lithium. It would be unwise clinically to assume that all putative mood-stabilizing agents provide similar protection against suicide or other impulsive or dangerous behaviors.

For example, findings from recent reports from a multicenter European collaborative study challenge the assumption that all effective mood-altering treatments have a similar impact on suicide rates. This study found no suicidal acts among bipolar and schizoaffective disorder patients maintained on lithium, whereas carbamazepine treatment was associated with a significantly higher rate of suicides and suicide attempts in 1% to 2% of subjects per year-at-risk. (60, 61) Patients assigned to carbamazepine had not been discontinued from lithium (B. Müller-Oerlinghausen, written communication, May 1997), which might otherwise have increased risk iatrogerically. (8, 42-46) A similar rate of suicide attempts to that found with carbamazepine in bipolar patients was also found among patients with recurrent unipolar depression who were maintained long-term on amitriptyline, with or without a neuroleptic. (60, 61) These provocative observations regarding carbamazepine and amitriptyline indicate the need for specific assessments of other proposed alternatives to lithium for their potential long-term protection against suicidal risk in bipolar disorder patients.

Several drugs are used empirically to treat bipolar disorder patients, although they remain largely untested for long-term, mood-stabilizing effectiveness. In addition to carbamazepine, these include the anticonvulsants valproic acid, gabapentin, lamotrigine, and topiramate. Sometimes calcium channel-blockers, such as verapamil, nifedipine, and nimodipine, are employed, and newer, atypical antipsychotic agents including clozapine and olanzapine are increasingly used to treat bipolar disorder patients, encouraged in part by an assumption that risk of tardive dyskinesia is low. The potential antisuicide effectiveness of these agents remains unexamined. An exception to this pattern is clozapine, for which there is some evidence of antisuicidal and perhaps other antiaggressive effects, at least in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. (62) Clozapine is sometimes used, and may be effective, in patients with otherwise treatment-unresponsive major affective or schizoaffective disorders (63, 64), but its antisuicidal effects in bipolar disorder patients have yet to be investigated. Contrary to the hypothesis that serotonergic activity may contribute to antisuicidal effects, clozapine has prominent antiserotonin activity, particularly at 5-HT2A receptors (65, 66), suggesting that other mechanisms may contribute to its reported antisuicidal effects.

EFFECTS OF DISCONTINUING LITHIUM ON SUICIDE RISK

Another factor to consider in interpreting the findings pertaining to effects of lithium treatment on suicide rates is that most of the studies analyzed involved comparisons of suicide rates during vs after discontinuing long-term lithium treatment. In a recent international collaborative study, we found that clinical discontinuation of lithium maintenance treatment was associated with a sharp increase in suicidal risk in a large, retrospectively analyzed sample of bipolar I and II patients.(8, 9, 20, 21, 46) Rates of suicide attempts had decreased by more than six-fold during lithium maintenance treatment, compared to years between onset of illness and the start of sustained maintenance treatment (Table 2). In these patients, nearly 90% of life-threatening suicide attempts and suicides occurred during depressive or dysphoric mixed-mood states, and previous severe depression, prior suicide attempts, and younger age at onset of illness significantly predicted suicidal acts.

In striking contrast, after discontinuing lithium (typically at the patient's insistence following prolonged stability) rates of suicides and attempts increased 14-fold overall (Table 2). In the first year after discontinuing lithium, affective illness recurred in two thirds of patients, and rates of suicide attempts plus fatalities increased 20-fold. Suicides were nearly 13 times more frequent after discontinuing lithium (Table 2). Of note, at times later than the first year off lithium, suicide rates were virtually identical to those estimated for the years between onset of illness and the start of sustained lithium maintenance. These findings strongly suggest that lithium discontinuation carries added risk, not only of early recurrence of affective morbidity, but also of a sharp increase in suicidal behavior to levels well in excess of rates found before treatment, or at times later than a year after discontinuing treatment. These increased suicidal risks may be related to a stressful impact of treatment discontinuation itself that may have contributed to most of the contrasts shown in Table 1 between subjects treated with lithium vs subjects who discontinued lithium use.(8)

If stopping lithium is followed by added suicide risk associated with recurrence of bipolar depression or dysphoria, then slow discontinuation of treatment may reduce the incidence of suicide. Encouraging preliminary findings indicated that, after gradual discontinuation of lithium over several weeks, suicidal risk was reduced by half (Table 2).(9, 21) The median time to first recurring episodes of illness was increased an average of four times after gradual vs rapid or abrupt discontinuation of lithium and the median time to bipolar depression was delayed by about threefold. (8, 45, 46) The apparent protective effect of gradually discontinuing lithium against suicidal risk may reflect the highly significant benefits of gradual discontinuation against early recurrences of affective episodes as a key intervening variable.(8)

CONCLUSIONS

Several points arising from this overview of the association of long-term lithium treatment with reduced suicide risk should be emphasized. First, the evidence reviewed provides strong, consistent support for the conclusion that suicide rates are much lower during long-term treatment with lithium than after stopping this treatment for patients with bipolar and perhaps other major recurrent affective or schizoaffective disorders. Second, these findings also indicate that much-needed studies of the therapeutics of suicide are feasible, at least based on naturalistic comparisons involving varied treatment conditions. Perhaps even controlled comparisons of clinically plausible alternative treatments can be carried out, as has been done to compare lithium and carbamazepine.(60, 61) Third, it is important to emphasize that the average protective effect of lithium is far from complete, and suicide rates during lithium treatment greatly exceed those in the general population. Fourth, the effect of lithium against suicide is not known to generalize to other effective or experimental mood-altering therapies, nor to conditions other than manic-depressive syndromes and perhaps some schizoaffective conditions, all of which require long-term studies comparing clinically and ethically plausible alternative treatment options.

In contrast to lithium, there is remarkably little information available concerning effects of alternative treatments on suicidal behavior, other than preliminary indications that carbamazepine may not be as effective as lithium in limiting suicidal risk in patients with bipolar or schizoaffective disorders (60-61), and that clozapine may have antisuicidal effects in patients with chronic psychotic disorders.(62) While it is plausible to expect a suicide-reducing benefit of effective antidepressant treatments in patients with major affective disorders, information supporting this hope remains remarkably limited and either inconclusive or negative. (11, 17, 30, 35-37)

Finally, if the impression is valid that lithium exerts less consistent protection against bipolar depression than against hypomania or mania, it follows that better protection against bipolar depression is a key to further limiting suicidal risk in bipolar disorders. The striking paucity of studies of treatment effectiveness in bipolar depression and the close association of suicidality and depression or dysphoria in bipolar disorders emphasize the need for improved identification and timely, sustained treatment of patients at increased risk of suicide with all forms of major depression, but particularly of bipolar depression.

-Information about the authors-

Dr. Tondo is research associate at McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, in Boston, MA; assistant professor of psychiatry in the Department of Psychology at the University of Cagliari in Sardinia, and director of the outpatient clinic Centro Lucio Bini, a Stanley Foundation International Research Center, in Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy.

Dr. Baldessarini is professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at Harvard Medical School in Boston; director of the Laboratories for Psychiatric Research, Bipolar & Psychotic Disorders Program, and the Psychopharmacology Program, at the McLean Division of Massachusetts General Hospital in Belmont, MA; a founding director of the International Consortium for Bipolar Disorders Research.

Dr. Hennen is instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston and chief of the Biostatistics Laboratory of the Bipolar & Psychotic Disorders Program at McLean Hospital.

Acknowledgements: Completion of this article was supported by awards from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Theodore & Vada Stanley Foundation, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (LT); and by National Institutes of Health Career Investigator Award MH-47370, the McLean Private Donor Neuropharmacology Research Fund, a grant from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, and an award from Solvay Corporation (RJB).

This article was previously published in Primary Psychiatry. 1999;6(9):51-56Those with Early-Onset of Bipolar Disorder Also Shown More Likely to Respond to Symbyax Treatment

May 05, 2004 -- New data show that Symbyax™ (olanzapine and fluoxetine HCl) reduced the symptoms associated with suicidal ideation (having thoughts of suicide), a predictor of suicidal behavior, in bipolar depressed patients within the first week of treatment. Another study demonstrated that having an early onset of bipolar disorder tripled the likelihood that a patient might respond to Symbyax. These findings were presented today at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Symbyax is the first and only FDA-approved treatment for the depressive phase of bipolar disorder.

"These data provide hope to patients whose lives are disrupted by bipolar depression, a devastating and difficult condition to treat that often results in suicide or suicide attempts," said Terence A. Ketter, M.D., associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and chief, Bipolar Disorders Clinic, Stanford University School of Medicine. "The rapid reduction of symptoms associated with suicidal ideation suggests the potential benefit of Symbyax among bipolar depressed patients, who are at high risk of taking their own lives."

Key Findings

Suicidal Ideation Study

An eight-week analysis of 688 people that compared Symbyax (n=73), olanzapine (n=299) and placebo (n=316) in the treatment of bipolar I depression showed:

Olanzapine is not indicated for bipolar depression.

Predictors of Response Study

In addition, a statistical analysis performed on acute phase data from a double-blind, randomized clinical trial comparing Symbyax (n=86), olanzapine (n=370) and placebo (n=377) in patients with bipolar depression found:

"Since bipolar disorder often emerges in late adolescence or early adulthood, the high rates of response among bipolar depressed patients who had early onset suggests that Symbyax may work well in this large, well-defined population," said Robert W. Baker, M.D., associate medical director, USMD Neurosciences, Eli Lilly and Company.

About Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder typically emerges in adolescence or young adulthood, and episodes continue intermittently throughout life, often disrupting work, school, family, and social life.

|

Patients with the disease have a higher risk of committing suicide than those with other psychiatric or medical disorders, and without effective treatment, bipolar disorder can lead to suicide in nearly 20 percent of cases. The relative risk of suicide among patients with bipolar depression has been shown to be nearly 35 times greater than among patients in the manic phase of bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness, affects an individual's mood, behavior, and thinking. Unlike many illnesses, symptoms may be quite different at various phases of the illness. Treatment is challenging because some therapies that are effective for one phase of the illness may be counterproductive for another. For example, antidepressant treatments can precipitate manic episodes.

Bipolar disorder is a complex mental illness characterized by debilitating mood swings ranging from episodes of deep depression (feelings of extreme guilt, sadness, anxiety and, at times, suicidal thoughts) to episodes of mania (abnormal euphoria, elation and irritability), interspersed with periods of normal mood. Patients with bipolar disorder spend more than three times longer in the depressive phase than in the manic phase of the disorder and take longer to recover from it.

More than 2.5 million Americans live with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder but recent research indicates the real number may be as high as 10 million. The results of untreated bipolar disorder can be catastrophic. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, nearly one in every five people with the illness commits suicide. The World Health Organization estimates that bipolar disorder is the sixth leading cause of disability in the world.

Important Information About Symbyax

The most common treatment-emergent adverse event associated with Symbyax (vs. placebo) in clinical trials was somnolence (22 vs. 11%). Other common events were: weight gain (21 vs. 3%), increased appetite (16 vs. 4%), asthenia (15 vs. 3%), peripheral edema (8 vs. 1%), tremor (8 vs. 3%), pharyngitis (6 vs. 3%), abnormal thinking (6 vs. 3%) and edema (5 vs. 0%).

Contraindications - Symbyax should not be used with an MAOI or within at least 14 days of discontinuing an MAOI. At least five weeks should be allowed after stopping Symbyax before starting an MAOI. Thioridazine should not be given with Symbyax or within at least five weeks after stopping Symbyax. Symbyax is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to the product or any component of the product.

Hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus - Hyperglycemia, in some cases associated with ketoacidosis, coma or death, has been reported in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics including olanzapine alone, as well as olanzapine taken concomitantly with fluoxetine. All patients taking atypicals should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia. Persons with diabetes who are started on atypicals should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control; those with risk factors for diabetes should undergo baseline and periodic fasting blood glucose testing. Patients who develop symptoms of hyperglycemia during treatment should undergo fasting blood glucose testing.

Cerebrovascular adverse events (CVAE), including stroke, in elderly patients with dementia - Cerebrovascular adverse events (e.g., stroke, transient ischemic attack), including fatalities, were reported in patients in trials of olanzapine in elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis. In placebo-controlled trials, there was a significantly higher incidence of CVAE in patients treated with olanzapine compared to patients treated with placebo. Olanzapine is not approved for the treatment of patients with dementia-related psychosis.

Orthostatic hypotension - Symbyax may induce orthostatic hypotension associated with dizziness, tachycardia, bradycardia, and in some patients, syncope, especially during the initial dose-titration period. Particular caution should be used in patients with known cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, or those predisposed to hypotension.

Allergic events and rash - In premarketing trials, the overall incidence of rash or allergic events with Symbyax was similar to that with placebo (4.6%, 26/571 vs. 5.2%, 25/477). In fluoxetine clinical studies, 7% of 10,782 fluoxetine-treated patients developed various types of rashes and/or urticaria. If rash or other possibly allergic phenomena appear for which an alternative etiology cannot be determined, immediate discontinuation is recommended.

Concomitant use - Caution should be used when prescribing medications that contain olanzapine or fluoxetine HCl with Symbyax.

Abnormal bleeding - Patients should be cautioned regarding the risk of bleeding associated with the concomitant use of Symbyax with NSAIDs, aspirin, or other drugs that affect coagulation.

Mania/hypomania - Because of the cyclical nature of bipolar disorder, patients should be monitored closely for the development of symptoms of mania/hypomania during treatment with Symbyax.

Prolactin and serum sodium - As with other drugs that antagonize dopamine receptors, Symbyax elevates prolactin levels, and a modest elevation persists during administration; however, possibly associated clinical manifestations were infrequently observed. Hyponatremia has been observed in premarketing studies of Symbyax, but the incidence of serum sodium levels occurring below the reference range was statistically insignificant compared with placebo (2%, 10/500 vs. 0.5%, 2/380); none of these patients had a treatment-emergent level less than 130 mmol/L.

Transient, asymptomatic elevations of hepatic transaminase - In premarketing trials, statistically significant ALT (SGPT) elevations (>3 times the upper limit of the normal range) were observed in 6.3% (31/495) of patients exposed to Symbyax compared with 0.5% (2/384) of the placebo patients and 4.5% (25/560) of olanzapine-treated patients. None of these patients developed jaundice. Periodic assessment of transaminases is recommended in patients with significant hepatic disease.

Weight gain - In clinical studies, the mean weight gain for Symbyax-treated patients was statistically significantly greater than placebo-treated (3.6 kg vs. -0.3 kg) and fluoxetine-treated (3.6 kg vs. -0.7 kg) patients but was not statistically significantly different from olanzapine-treated patients (3.6 kg vs. 3.0 kg). Fourteen percent of Symbyax-treated patients met criterion for having gained >10% of their baseline weight.

Special populations and elderly - Dysphagia was observed infrequently in premarketing studies, but as with other psychotropic drugs, Symbyax should be used cautiously in patients at risk for aspiration pneumonia. Esophageal dysmotility and aspiration have been associated with antipsychotic drug use. In 2 clinical studies in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, two olanzapine-treated patients died from aspiration pneumonia, with one of these patients experiencing dysphagia. As with other CNS-active drugs, Symbyax should be used with caution in elderly patients with dementia. The lowest starting dose should be considered in patients with hepatic impairment.

As with all medications that contain an antipsychotic, the following considerations should be taken into account when prescribing Symbyax:

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) - as with all antipsychotic medications, a rare condition known as NMS has been reported with olanzapine. If signs and symptoms appear, immediate discontinuation is recommended.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) - as with all antipsychotic medications, prescribing should be consistent with the need to minimize the risk of TD. If its signs and symptoms appear, discontinuation should be considered.

Seizures - occurred infrequently in premarketing clinical trials (4/2066, 0.2%). Confounding factors may have contributed to many of these occurrences. Symbyax should be used cautiously in patients with a history of seizures or with conditions that lower the seizure threshold. Such conditions may be more prevalent in patients age 65 years or older.

Source: Eli Lilly Press Release

"Although suicide is the major complication of [bipolar] disorder, many bipolar patients never attempt suicide and there may thus be a difference between those who do and do not attempt suicide at least once," note Frédéric Slama (Hôpital Henri, Creteil, France) and colleagues.

With this in mind, the team studied 307 people diagnosed with bipolar I or II disorder. They used the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies, and the Family Interview for Genetic Studies to determine the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and its lifetime description, as well as lifetime comorbid axis I disorders, familial history of psychiatric disorders, and demographic characteristics.

In all, 129 (42%) of the participants had made at least one suicide attempt in their life. The risk of suicide attempt was associated with early onset of bipolar disease, numerous depressive episodes, history of antidepressant-induced mania, and a familial history of suicidal behavior.

Suicide attempt was also more likely among patients with lifetime occurrence of alcohol abuse, but the researchers note that this is unlikely to be specific to bipolar patients, as it has often been reported in nonbipolar suicide as well.

Interestingly, no association between suicide attempt and gender or diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder was observed. In addition, following multivariate analysis, social phobias, tobacco use, and personal history of head injury were not associated with suicidal behavior.

"In conclusion, in bipolar patients, a severe outcome (high number of depressive episodes, early age at onset, history of antidepressant-induced mania), comorbid alcohol abuse, and familial history of suicidal behavior may constitute major warning characteristics to identify subgroups at risk of suicidal behavior," the team writes in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

"In clinical practice, these characteristics should be

systematically assessed."

Source:

Background: Suicide is the most severe and frequent complication of bipolar disorder, but little is known about the clinical characteristics of bipolar patients at risk of suicide. The purpose of this study was to identify those characteristics.

Method: We studied 307 prospectively recruited DSM-IV-diagnosed bipolar I or II patients from November 1994 through October 2001. Semi-structured diagnostic interviews (the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies and the Family Interview for Genetic Studies) were used to determine the diagnosis of bipolar disorder and its lifetime description, lifetime comorbid Axis I disorder diagnoses, familial history of psychiatric disorders and demographic characteristics.

Results: One hundred twenty-nine bipolar patients (42%) had made at least 1 suicide attempt in their life. Lifetime history of suicidal behavior was associated with history of suicidal behavior in first-degree relatives but not with a familial history of mood disorder. Early age at onset of mood disorder, total number of previous depressive episodes, alcohol and tobacco use, social phobia, antidepressant-induced mania, and personal history of head injury were associated with suicidal behavior. No association was observed with gender or diagnosis of bipolar I or II disorder. Social phobias, tobacco use, and personal history of head injury were no longer associated with suicidal behavior in the multivariate analysis.

Conclusion: Bipolar patients with early age at bipolar disorder onset, high number of depressive episodes, personal history of antidepressant-induced mania, comorbid alcohol abuse, and suicidal behavior constitute a clinical subgroup at risk of suicidal behavior. This information, as well as familial history of suicide behavior, should improve suicide risk assessment in bipolar patients.

(J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:1035-1039)